By Sarah Eager

For centuries, our understanding of the ocean has been shaped not only by science but by stories, myths, literature, and visual media. While many narratives celebrate the beauty and mystery of marine creatures, a significant number have portrayed marine predators in an ominous, threatening light. Such portrayals have had profound real-world consequence, affecting conservation efforts, fishing practices, and public perception, often to the detriment of entire ecosystems.

“Sharks are not the monsters people think they are.”

- Peter Benchley, The Guardian

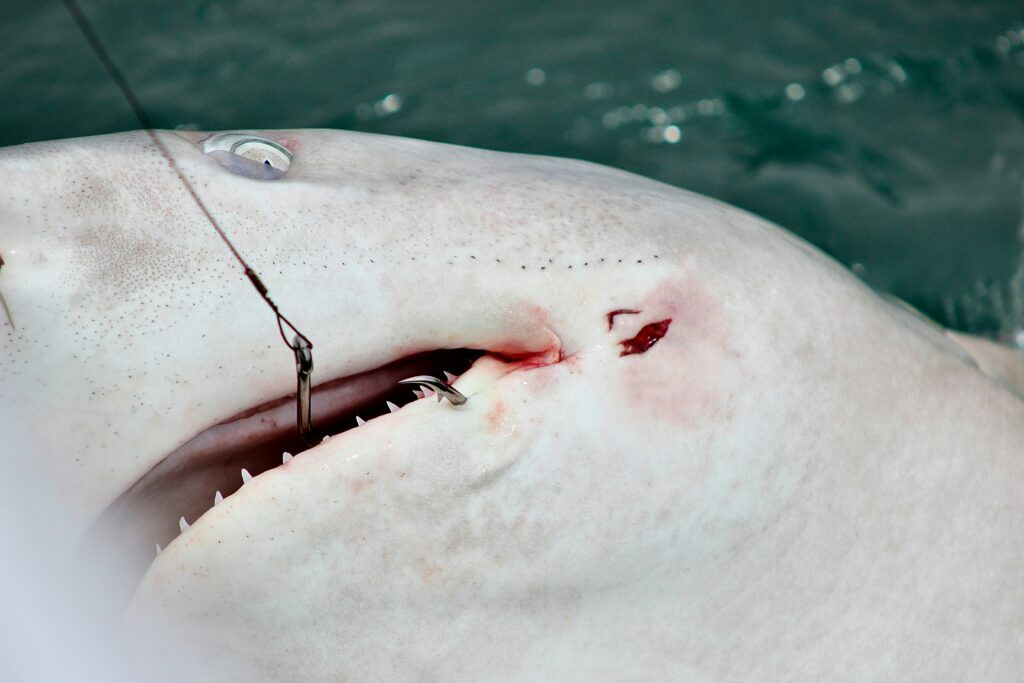

Great White Shark, by Oleksandr Sushko on UnSplash

The birth of fear

When it comes to marine animals depicted negatively, few suffer more than sharks. The widespread cultural fear started with Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel Jaws and, the following year, Steven Spielberg’s film adaptation. The story of a great white shark terrorising a sleepy beach town captivated audiences, but also instilled a lasting image of sharks as ruthless maneaters.

Most authors dream of their work having a widespread, lasting impact, but Benchley later regretted his novel. In an interview he admits, “What I know now, which wasn’t known when I wrote Jaws, is that there is no such thing as a rogue shark.”

It wasn’t until the film’s release that Jaws left an indelible mark on public consciousness, amplifying the portrayal of a merciless, lurking monster. The film became an overnight sensation, producing monster tropes that persist to this day and firmly establishing the great white shark as not just a pop culture icon, but an oceanic enemy number one. Despite this success, Spielberg echoes Benchley’s sentiments, stating that the impact on the shark population is something “I truly and to this day regret.”

Image by Gerald Schombs on UnSplash

“During the summer of 1975 when Jaws was in hundreds of theatres across the US… we could see the fear that it was stirring up,” says Wendy Benchley, Peter’s wife and a prominent ocean conservationist. In some, this fear surfaced as a simple reluctance to go to the beach, while others chose to emulate the film’s protagonists and hunt down the creature depicted in the film.

Feeding the fear

Jaws may have helped kick off the public’s fear of sharks, but Shark Week took that fear to new heights.

Launched in 1988, Shark Week greatly popularised sharks but also sensationalised attacks – it’s far more about spectacle than science. By consistently favouring fear-driven narratives and dramatised storytelling over balanced, factual content, the franchise has considerably shaped public perception, with serious repercussions for conservation efforts, policy, and the survival of shark populations.

White shark biologist Dr. Alison Towner, who studies shark conservation, notes that dramatised shows “may be fun, but they reinforce harmful stereotypes that make shark conservation harder.” Photographer Euan Rannachan laments “the Hollywood stereotypes they [sharks] usually get labelled with.” Sharks are vulnerable -they need protection, not fear. But fear sells.

Fear sells

“Fear is an effective framing device, particularly if the objective is to obtain an audience’s attention or support, or incite particular emotional responses and behaviour,” say researchers who look at the media’s role in public and political response to fatal human-shark interactions. This reliance on fear and excitement to drive engagement can be seen in the terminology used to describe sharks. Vivid terms like “attack”, “man-eater”, “bloodthirsty”, and “rogue” have long been used to describe sharks in literature, films, and the media, while seas with shark populations are described as “shark-infested waters”.

A study analysing Shark Week over a 32-year period looked at the frequency of words with negative connotations used in episode titles, including: “attack”, “deadly”, “monster”, and “man-eater”. The study found a high frequency of fear-mongering language and that Shark Week consistently “portrays sharks negatively, airs falsehoods, and does not adequately represent shark scientists.”

Between 1988 and 2020, almost half of all episodes contained negatively charged and sensationalised titles, and in 2002, more than 75% of episodes released featured negative words and phrases. Of the 201 episodes analysed, 74% relied on shark bites and attacks to build threat narratives, and dramatic tag lines reinforced a negative image, while less than 3% provided action-based advice for supporting shark conservation, such as donating to conservation efforts.

More than 50% of episodes contained graphic re-enactments and negative depictions, a tactic that’s found to increase viewers’ fear, often overshadowing brief conservation blurbs. Violent shark imagery leads to greater fear, making viewers more likely to support culling, beach nets, or other lethal measures -even when followed by conservation messages. Far from being an educational series, Shark Week has often functioned more like a horror franchise. It’s an editorial strategy that plays well with audiences hungry for adrenaline but poorly serves public understanding of sharks.

“It’s not doing the sharks any favours,” says Lisa Whitenack, a shark paleobiologist and co-author of the study. Additionally, the study found a significant lack of scientists and experts featured in episodes – Whitenack states that the message the creators are sending is that they’re just “not as worried about representing good science.”

Shark Week’s impact has also been documented in digital sentiment analysis. The findings from an analysis of social media posts during Shark Week seasons showed that viewers’ posts skewed significantly more negative, with a noticeable uptick in words related to “attack”, “fear”, and “hate”. The timing and scale of that negativity suggests that Shark Week actively shapes real-time public perception.

Outside of Shark Week, an analysis of 2,000 Facebook posts by Australian news and media outlets and public users’ comments found a common theme: the ocean is dangerous. Over half of the articles reported elevated public risk, with the most frequent topics being shark bites and threats; 60% of the articles analysed were framed towards the negative impacts of sharks on humans, and 46% included negative shark and human interactions. An analysis of newspaper articles from Sydney, Cape Town, and Florida to determine how the word “attack” was used in the context of sharks found that Cape Town articles included “attack” once for every 107 words. In contrast, Sydney articles used “attack” most often, an average of six times per article. Shark coverage in news media is disproportionate: over half of news stories focus on “attacks”, while only 11% discuss conservation.

Collection of shark attack headlines

In recent years, Shark Week has slowly begun to shift its messaging, but it often falls short. While sharks continue to be more often portrayed negatively than positively, 53% of episodes mentioned, though only briefly, the importance of shark conservation and sharks’ role in the ecosystem. There’s also a greater focus on research: 75% of episodes released in 2017 were at least partly research-based compared to 100% of episodes in 2001 categorized as shark bites. Yet, the emphasis on dramatic music, shark-bite survivors, melodramatic titles, and fictionalised scenarios continues to undermine any scientific or positive content. Whitenack describes Shark Week coverage as “a whole lot of negative with a quick positive statement or a quick pro-conservation statement at the end.”

Exposure to balanced episodes increases viewers’ willingness to support shark conservation by up to 40%. Biases and misperceptions track closely with “aggregate media coverage”, and exposure to media coverage of shark bites is closely linked with beliefs that these events are common. However, Whitenack says that kind of “contradictory messaging” isn’t helpful.

Another survey by Jason O’Bryhim states that the media can play a significant role in promoting conservation, but unfortunately “media coverage of sharks has been controversial.”

“Creating positive attitudes toward sharks and their conservation is critical,” O’Bryhim claims. “Attitudes have the ability to guide, influence, direct, shape, or predict an individual’s potential behaviour toward a species and its conservation.”

Looking at 2025’s Shark Week line-up, there’s likely little chance of shaping positive public attitudes, with titles such as: “Great White Reign of Terror”, “Florida’s Death Beach”, “Attack of the Devil Shark”, “Great White Assassins”, and “Death Down Under”.

Image by Lothar Boris Piltz on UnSplash

Meanwhile, other documentaries, like Blue Planet II (2017), narrated by David Attenborough, have painted a much more nuanced picture of marine life. Attenborough emphasises that the ocean is not a place of monsters, but a delicate ecosystem that we must strive to understand and protect. Blackfish (2013) shows us the pivotal role media plays in shifting public perception. The film’s impact led SeaWorld to end its orca breeding programs and shows, while attendance dropped by 84% following its release – proof that the media can spur positive change.

Real world impact

“Once people felt that sharks could come after them, fear of sharks skyrocketed in a way never seen before.”

– Christopher Pepin-Neff

The consequences of these media frenzies are tangible. Fears, fuelled by the media, result in dramatic reductions of shark populations. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that, globally, 100 million sharks are killed each year, with overfishing and finning driven by a combination of demand and fear-based policies. Many shark species have seen population declines of up to 90% in recent years, and sharks and rays are now some of the most threatened species, in large part due to “overexploitation exacerbated by negative human perceptions.”

These fictionalised narratives have even been weaponised to influence controversial Western Australian shark-culling policies, killing tens of thousands of sharks annually due to ill-perceived threats to humans. In Florida, where shark attacks have often been sensationalised in the media, shark hunting was legalised and expanded, killing thousands of sharks per year. This so-called ‘Jaws’ effect rests on three perceived tenets: “the intentionality of the shark, perception that these events are fatal, and the belief that ‘the shark’ must be killed.” Fear of sharks is directly related to whether people think the shark is intentional in its actions.

Image by Hvlck NubrW on UnSplash

Similarly, shark hunting and sporting events like Monster Shark Tournaments off the US East Coast feed the perception of sharks as conquests, the killing of which constitutes some kind of legitimate civic duty.

Local fishing communities often support culling, citing safety and protection of fish stocks. But, as apex predators, sharks occupy vital ecological roles. They regulate marine ecosystems and maintain balance and biodiversity, contributing to the overall health of the ocean. Yet, unfair depictions have led to alarming declines worldwide. Removing apex predators destabilises marine food webs, causing prey species and mid-level predators to proliferate, and introduces imbalances that can devastate reefs, seagrass beds, and even collapse fisheries. These trophic disruptions reduce ecosystems’ resilience to stressors, including climate change.

An analysis of shark population data in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean found that of the sharks present, 11 species consumed cownose rays. Over a 30-year period, all 11 shark species declined significantly; meanwhile, the cownose ray population experienced a rapid resurgence along the Mid-Atlantic coast and in the waters surrounding North Carolina bay scallop fisheries. This population increase is due to the steep decline of the sharks that prey on these rays, say researchers. As these rays breed unchecked, their demand for prey (clams, oysters, scallops) has outpaced the ability of the prey species to replenish its own stock. The shark’s regression can be felt all through the food chain – bay scallop numbers fell so low that North Carolina had to close its scallop fisheries that had flourished on its shores for well over a century.

Similarly, in Japan, intense fishing of apex predators caused a population boom of longheaded eagle rays. This increase, in turn, decimated both wild and maricultured shellfish stocks. Coral ecosystems have equally seen profound disruptions, with shark population declines threatening 11% of ecological functions and approximately 18% of megafauna species by the end of the century.

Rewriting the story

Image by NOAA on UnSplash

The history of marine life in media is a story of fear, misunderstanding, and exploitation. From Jaws to Shark Week, these portrayals have shaped behaviours that damage marine populations and ecosystems.

When fear prevails over facts, representation is sacrificed for ratings, and entertainment side lines conservation, sharks suffer. Still, the opportunity exists: Shark Week can recalibrate its lens, prioritising conservation narratives, balancing thrill with truth, and offering clear paths for viewers to support marine initiatives. With millions watching every summer, transforming fear into fascination isn’t just good storytelling… it could help reverse devastating shark population declines.

Take a look at our ‘Save The Ocean – Save Sharks’ collection.